Monday, November 30, 2009

this is our god.

Posted by Claire Aufhammer at 12:15 PM 0 comments

Friday, November 20, 2009

a revolutionary revelation.

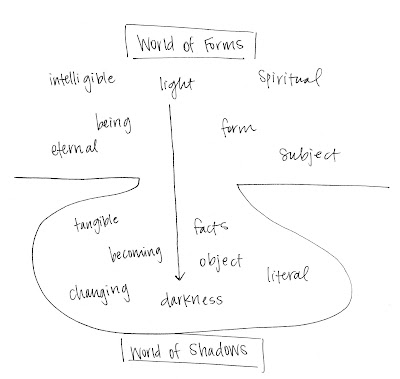

The magnitude of the incarnation of the divine through the person of Jesus Christ is lost in the Gospels’ translation from Greek to English. These inspired accounts of Jesus’ life and ministry speak uniquely to the first-century Jew and Gentile. As such, our understanding of the Gospels is made more complete when we look at the person of Christ from the worldviews and perspectives that dominated the culture of that day.

Posted by Claire Aufhammer at 2:39 PM 0 comments

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

understanding divinity.

This is an essay I very recently turned in for my favorite class, Literary Bible. It's long, I know, but I wanted to share it with you.

Francis Petrarch once posed the question, “What is theology, if not poetry about God?” His inquiry suggests a connection between poetry and “the science of things divine,” as The Oxford English Dictionary defines “theology.” This supposition that divine knowledge may be acquired best in the figurative sense aligns with a statement made by Thomas Aquinas:

Poetic knowledge is of things which, on account of a defect of truth, cannot be grasped by reason, and that is why reason must be seduced by a certain likeness; theology, however, concerns things which are above reason. The symbolic mode is common to them both, therefore, because neither is precisely proportional to reason.

Both of these statements share the idea that basic modes of reason are insufficient means of attaining knowledge of the heavenly realm. These men recognize that the finite minds of humans are unable to comprehend things divine in nature. Reason alone does not, cannot, and will not produce full knowledge. Thus, figurative language becomes a necessary means to acquire an understanding of that which is beyond our literal world. As Jesus demonstrates in Mark 4 however, symbolic discourse does not always usher in a complete understanding of the divine. Rather, his explanation of his parables reveals an underlying supposition that our knowledge of God is not under our control; these parables and figurative stories lay truth in the hearts of men, but the Spirit brings final revelation to our limited perception.

In this sense, poetry only acts as a partial bridge between the end of our ability to know and the beginning of divine truth. As defined by The Oxford English Dictionary, “poetry is the expression or embodiment of beautiful or elevated thought, imagination, or feeling in language adapted to stir the imagination and emotions.” It arouses within readers an emotional response. Its imagery illuminates truth. It speaks to the deepest part of the soul. It is “the art by which the poet projects feeling and experience onto an imaginative plane, in rhythmical words” (Funk and Wagnall’s Standard Dictionary: International Edition). As a result, poetry has the potential to reveal the qualities and character of the poet as they are projected into verse. But often its ability to do so is incomplete, as Jesus’ parables demonstrate.

When Jesus descended the throne and entered humanity, his main mode of discourse was allegorical. He, both divine and human, recognized our inability to comprehend by reason alone so he taught using parables. Though not exactly metrical verse, these culturally relevant metaphors infused with moral lessons were very similar to poetry. Their symbolism spoke to the heart and stirred emotion using figurative language. In this way, wisdom of the heart, chokmah, was nurtured, and knowledge of the divine was then fostered. In essence, he seduced reason into that “certain likeness,” of which Aquinas spoke. At the same time however, few people understood the meaning of these metaphors. So although figurative language brings us closer to comprehension of the truth, as Petrarch and Aquinas assert, we are still reliant on another to usher in complete revelation; Someone must reveal the truth to us.

Just after telling a large crowd the parable of the sower, Jesus opposes the notion that symbolic language divulges understanding. Concerned that his parables cause more confusion and unrest than necessary, the twelve disciples question Jesus. In response, he says to them, “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside everything is in parables, so that they may indeed see but not perceive, and may indeed hear but not understand, lest they should turn and be forgiven” (Mark 4:11-12). In saying this, Jesus refutes that figurative language makes things easier to understand. Rather, he confesses that some will not understand the parables, and those who do not understand the parables will not understand the truth. It is here that the beginnings of the notion of an incomplete comprehension of the divine manifests. For even the disciples, who have been given the secret, are unable to grasp the truth. And if those closest to him cannot understand him, others might not either. As a result, the chasm between own human finitude and God’s incalculable nature is made obvious.

Jesus further expounds on this concept of knowing by explaining the parable of the sower to his disciples. He first establishes that the seed being sown is the word. This word is the Gospel, the good news, the truth. In Greek, it may be translated as logos, or the reason and the argument. In Hebrew, it may be translated as dabar, or the word and the action. Regardless, this word is that through which revelation is revealed, and this word is sown. Here, an emphasis falls on the idea that truth comes to believers; believers do not reach the truth by their own means. The division between God and us is far too wide for us to cross on our own. Thus, the idea that Something or Someone intercedes for us offers hope that the truth can be grasped.

Jesus continues to discuss the understanding of parables as he proceeds to assert that the different types of soil in this parable are representative of the different types of people. The effects of the environment surrounding the individual and the state of their heart affect the way they receive the word. In most people, the word is choked or does not last. But in some it is sustained: “those that were sown on the good soil are the ones who hear the word and accept it and bear fruit, thirtyfold, and sixtyfold, and a hundredfold” (Mark 4:20). In some people, the word does mean something. Because their hearts have received the word, they now have wisdom of the heart, or chokmah. In these people, the word produces radical results. Yet it is not by any work of these individuals. Rather, it is the work of the Lord. Later on, Jesus explains this, “The kingdom of God is as if a man should scatter seed on the ground. He sleeps and rises night and day, and the seed sprouts and grows; he knows not how” (Mark 4:20-21). Regardless of the man’s actions, the seed sprouts, and he is dumbfounded. The mystery of a seed’s growth is reiterated in the following parable:

With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable shall we use for it? It is like a grain of mustard seed, which, when sown on the ground, is the smallest of all seeds on earth, yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes larger than all the garden plants and puts out large branches. (Mark 4:30-32)

So what by nature appears to be small and insignificant, God makes larger than imaginable.[1] Like the seed, our understanding of truth grows. As these two parables indicate, however, a seed’s growth is not by our own works. The truth manifests itself in us not on our own terms, but rather, on the terms of another Being who sustains its growth. So ultimately, our understanding comes from God.[2] As a result, we are dependant on him for knowledge. So while the figurative brings us closer to revelation, we ultimately find ourselves reliant on God for complete comprehension.

Though hard for our finite minds to apprehend, these parables reveal to us God’s nature. His complexities, like the parables, are not easily discernible; he remains shrouded in mystery. But in the same way that our understanding of Jesus’ teaching is on God’s terms, so is our understanding of God himself. The author of Mark notes that after receiving Jesus’ words and witnessing the calming of the storm, “they were filled with fear and said to one another, ‘Who then is this, that even the wind and sea obey him?’” (Mark 4:41). Though not necessarily a concrete revelation of who God is, this question is representative of the disciples’ journey to discover their rabbi’s identity. We can be sure of this because fear of the Lord ushers in wisdom.[3] This place of fear is humbling; it reminds us of our place in life, the chasm between God and ourselves, and thus our own insufficiency. Yet in this place, we acquire wisdom as God’s Spirit reveals him to us in his timing. We will begin to see that he is strong—strong enough to cause the small to become great, strong enough to calm storms on the sea. We will see that he is love—for what other reason would someone choose to cherish the broken. In the end, our revelation of the nature of God is concluded because the Spirit inclines himself to us, completing what the figurative introduced.

As Petrarch and Aquinas stated, reason alone cannot usher in understanding of the heavenly realm. Their conclusion, however, that the symbolic mode brings full comprehension is not sufficient either. As Jesus demonstrates to his disciples in Mark 4, what is figurative is more often puzzling than enlightening. And though his parables are not poems, they are figurative in their symbolism. Mostly, they illustrate that while the parabolic does bring us closer to understanding the truth than does reason, it is still incomplete. For, as the parable of the sower exemplifies, full knowledge is not a result of our keen perception. Rather, it is a consequence of the grace bestowed us by an all-powerful God, who plants truth within us and is the cause of its growth. Our understanding of the “science of things divine” is contingent on that Divinity’s descent and offer of revelation to us.

[1] This mirrors Paul’s assertion in 1 Corinthians: “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are” (1:27).

[3] Proverbs 1:7 states, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge.”

Posted by Claire Aufhammer at 7:01 PM 2 comments

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

a call to justice and costly grace.

Posted by Claire Aufhammer at 10:16 PM 0 comments

we're all in this together.

Posted by Claire Aufhammer at 6:12 AM 0 comments